The Importance of Work Habits

I subscribe to James Clear’s emails, which are full of productivity tips. The latest article that I read described the scientific reason why our lives become chaotic without continuous effort to maintain order.

I subscribe to James Clear’s emails, which are full of productivity tips. The latest article that I read described the scientific reason why our lives become chaotic without continuous effort to maintain order.

I was already well aware of this phenomenon as it relates to managing a household. Think of how quickly laundry piles up, stacks of unopened mail spread across countertops, and dust becomes visible on the dining room table. If I don’t stay on top of these chores, the house looks completely cluttered.

Housework never ends.

Reading James Clear’s article made me think about how our jobs can become overwhelming and disordered if we don’t pay attention to regular tasks that provide structure and organization.

Email never ends, either.

I’m most effective at work when I stick to established habits. For example, as soon as I’ve sent or responded to an email, I either delete it or file it in my Outlook folder system. It prevents my mailbox from being clogged with messages I don’t need and lets me quickly locate the ones that I need to refer to later.

I have similar routines for managing paperwork and accounting tasks, but the habit that made the biggest difference in my work was making a point to write every day. Whether it was just a sentence or two, or revising paragraphs I’d already written, the daily effort kept my writing projects moving forward and trained my brain to get into “writing mode” more quickly. Even creative tasks benefit from habits that provide structure and predictability.

The more established our habits are, the easier it is to stay in control of our work.

Intent vs. Words

Not long ago I attended a City Hall meeting where a contentious topic was being reviewed. The council members were voting whether to continue pursuing a specific site to build a homeless shelter for men. The chambers were packed with community supporters on each side of the issue.

Not long ago I attended a City Hall meeting where a contentious topic was being reviewed. The council members were voting whether to continue pursuing a specific site to build a homeless shelter for men. The chambers were packed with community supporters on each side of the issue.

For much of the meeting, three of the elected officials were in favor and four were opposed. When it was time for each council member to explain their position, it was fascinating to listen to those who opposed the shelter. They each emphasized their compassion for homeless people but wanted more data, more options, and more time to think about the issue.

If you took their words at face value, it sounded fine. But those of us paying attention to the issue for many months knew that they already had the data and options that they referenced. Instead of honestly saying “no, I oppose the shelter because it’s controversial” they gave excuses and hid their true intent behind words that meant the opposite of their actions.

It was easy to spot their deception because they have a clear motive for trying to appease everybody: they want to get reelected!

In the workplace, it isn’t always easy to tell when someone’s intentions are different from their words. For example, if you ask your manager for a raise and they say they need to ask their leadership team whether budget is available, they are deflecting the responsibility to other people. It would be simple to tell you later that they would have liked to increased your salary, but it wasn’t possible. You would have a hard time learning whether that was true or not.

If you get the sense that someone is hiding their true intentions behind words that are meant to convince you of the opposite, you can always ask them to clarify. A great way to do this is to paraphrase back to them what you think they mean – not what they are actually saying.

Work Karma

It used to really bother me that leaders who abuse their authority often succeed in the workplace while ethical workers who perform their jobs well can easily be marginalized by those in power.

It used to really bother me that leaders who abuse their authority often succeed in the workplace while ethical workers who perform their jobs well can easily be marginalized by those in power.

I wanted work karma to punish bad managers and vindicate people whose careers were screwed over. I wanted fairness.

But most workplaces aren’t set up to reward good work and punish bad behavior. People-management systems reward those who please the people with power over their careers. Performance objectives such as cutting costs, launching successful products, or closing sales contracts matter more or less depending on who’s in charge.

Subjective, unwritten expectations have greater impact on individuals’ careers. Along with everyone else, leaders include their biases, perceptions, and fears when they make decisions about employees.

Have you ever had a manager who seemed to value everything you delivered? They had an assumption that you’re a strong worker and noticed every indicator that supported this idea.

Unfortunately, it also works the other way. If a manager dislikes you or decides you’re a poor performer, there’s not much you can do to change their opinion. There are plenty of ways to find fault in accomplishments when someone is determined to focus on the negative.

I’m still frustrated when good workers are mistreated and corrupt leaders get ahead, but I don’t dwell on it. I’d rather put my energy towards aligning my work with my values.

When Bad Ideas Happen to Good Employees

Recently a friend told me a funny story about one of his coworkers. His company hired someone to help them cut costs and reduce wasted time and materials. Essentially, his job was to make the company run more efficiently to increase profitability.

Recently a friend told me a funny story about one of his coworkers. His company hired someone to help them cut costs and reduce wasted time and materials. Essentially, his job was to make the company run more efficiently to increase profitability.

I was immediately interested in this story because I’m a big fan of efficiency. Or maybe just a big hater of wasted time and money. Either way, I know a bit about Lean Manufacturing Principles and Rapid Improvement Processes and was curious to know what techniques this person was using.

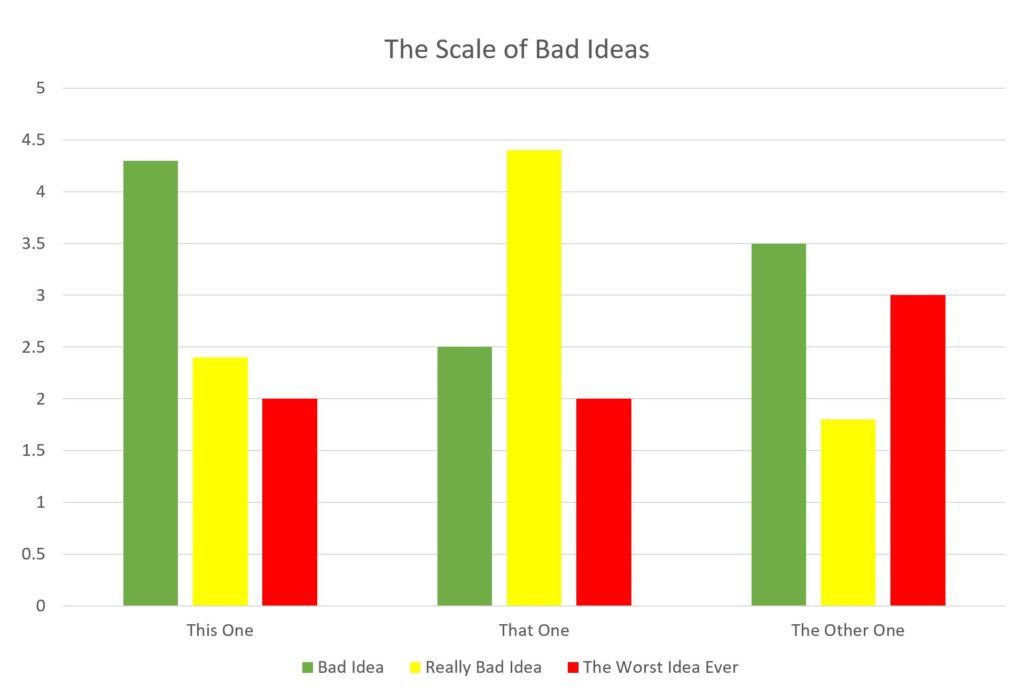

One of the processes he implemented required everyone who worked in their office to keep three colored cups at their workspaces. If everything was fine, they were supposed to display a green cup on the corner of their desk. If they had a non-urgent issue, they used a yellow cup, and the red cup was for when they needed their manager immediately.

By this point in the story I was already laughing, imagining a room full of adults being told they needed to use plastic drinkware to signal how well they were managing their work throughout the day.

I have no idea why the efficiency expert thought this was a good idea, or why he tried to implement it without getting buy-in from the staff first. If he had asked for feedback, he would have realized that nobody wanted to announce to their entire office when they had an issue they couldn’t resolve on their own. Plus, when people had questions, they just asked them, so it was solving a problem that didn’t exist.

But he didn’t get their feedback first, so everyone had to suffer through an office full of people sabotaging a process while feeling foolish and irritated.

Leading a team through a Rapid Improvement Process can have the complete opposite result. The surface-level benefit is that a work process that was slow, wasteful, or otherwise unpleasant is transformed for the better. But the real win is the positive impact in morale. When people are asked how their tasks could function more smoothly and work together as a team to create solutions, they feel valued, they are given some control over their work environment, and they bond during the process.

Tiny Decisions

When you feel stuck in a bad job, it can seem like there’s no good solution. The obvious choices are often weighty ones that have a big impact on your life.

When you feel stuck in a bad job, it can seem like there’s no good solution. The obvious choices are often weighty ones that have a big impact on your life.

Quit? Try a different career? Move to a new city?

A new job can change your hours, commute, paycheck, the type of people you spend your day with – in addition to changing what you actually do at work. It can be overwhelming to think about all the ways your life will be altered – and tempting to do nothing to avoid the risk of making the wrong decision.

But doing nothing keeps you feeling stuck.

You don’t have to make all-or-nothing decisions.

Making one tiny decision at a time reduces pressure and could ultimately create a better outcome. Each tiny decision has low stakes, so it doesn’t matter if you don’t like the results of any particular choice. Whether you like the results or not, you’ve got the feedback you need to help you make the next tiny decision.

For example, a common tiny decision would be looking at job postings for a company you think you’d enjoy working for. If you like what you read, the next tiny decision might be looking up employee reviews on Glassdoor. Or finding people who’ve worked there and ask them about their experience.

If at any point you don’t like what you’ve learned, you can stop going down that path and try a completely different tiny decision. Like taking a free online course in a subject that interests you. If you dislike it – quit. Then try something else. Maybe you are still interested in the topic, but reading articles about it will be a better fit than taking an online course.

Here’s an analogy for the difference between making one giant decision or a series of tiny decisions: A giant decision is like leaping from the starting point of a race to the finish line. Tiny decisions are like taking one step at a time, choosing where to put each footstep. The first way gets you there faster, and if you are confident that you’ll like the result – great. But if you’re unsure, smaller steps let you change direction more easily, while still propelling you forward.

Be Wary of Charismatic Leaders at Work

Throughout my career, there have been business leaders that inspired me to do my work with a deeper sense of purpose. I looked forward to their presentations at employee conferences and meetings because their speeches moved me. They clearly described their vision and how important it was for the team to achieve it. I left these events with fresh ideas for my projects and re-energized to complete them.

Throughout my career, there have been business leaders that inspired me to do my work with a deeper sense of purpose. I looked forward to their presentations at employee conferences and meetings because their speeches moved me. They clearly described their vision and how important it was for the team to achieve it. I left these events with fresh ideas for my projects and re-energized to complete them.

Time and time again, I was amazed at how smart and articulate they sounded. They described our mission in simple, easy to remember points, and gave us compelling reasons why we should care. They didn’t just make me think – they made me feel.

I give them credit for improving my strategies and plans because they made it easy for me to connect my work to the bigger goals of the organization. They strengthened my ability to get buy-in from other teams and leaders because I could show how my idea supported the top-down direction we were all supposed to follow.

So…great, right?

Not exactly.

Time and time again, these charismatic leaders disappointed me.

One leader dazzled me with his ability to get a room full of hundreds of people to enthusiastically commit to his vision. He got us to volunteer for additional work, and the vivid image of success that he described kept us focused for months. So it was confusing when after we delivered what he’d asked us to do, that nothing came of it. He didn’t take our front-line work and use his executive position to implement the goal we worked for.

I don’t know if his priorities had changed, if he lost interest in the goal, or if he simply lacked the ability to execute his vision. Plenty of people are very good at convincing others to support their ideas but lack the ability to push their projects to completion. Some of them have poor organization skills or get stuck when there are details to manage.

Unfortunately, this man was such a talented communicator that he got everyone excited about other things and moved on. The wasted time and potential was forgotten about.

Other charismatic leaders that failed me were more like empty vessels – appealing on the surface but not much inside. They think their only role is to imagine an outcome and inspire their followers to agree with them. Then they expect other people to figure everything else out because that kind of work is beneath them.

You can recognize this type of leader by their charming, magnetic personalities and the crowd of admirers that surround them. They will mesmerize employees with their strategic vision and big picture ideas but you won’t find them connected to the tactics, execution, or implementation.

The danger of this type of leader is that when people rally around an outcome without understanding the plan to achieve it, bad things can happen. Loyalty to the leader and an emotional attachment to the end-goal can cause workers to take unethical or even illegal actions. They might think the ends justify the means. Or, their fierce loyalty may convince them that they aren’t doing anything wrong.

The danger of this type of leader is that when people rally around an outcome without understanding the plan to achieve it, bad things can happen. Loyalty to the leader and an emotional attachment to the end-goal can cause workers to take unethical or even illegal actions. They might think the ends justify the means. Or, their fierce loyalty may convince them that they aren’t doing anything wrong.

Charismatic leadership isn’t at fault for every corporate scandal. Volkswagen’s emission-cheating has been blamed on a fearful, authoritarian climate led by ex-CEO Martin Winterkorn – but that is a negative leadership style for a different blog post.

There are, however, charismatic leaders at all levels of organizations and it isn’t necessarily the CEO that employees blindly follow. Imagine a beloved executive getting staff excited to break a sales record without having a specific plan for achieving the goal. This happens all the time! Lower level managers might be tempted to cut corners, and what starts out as a gray area can turn into misuse of funds, which then becomes fraud. An entire department can be swept along in unethical or illegal activity.

This isn’t to say that every charismatic leader is bad. The website Make A Dent Leadership has an interesting article by Shelley Holmes about positive and negative aspects of charismatic leadership.

As for me, I can only think of one such leader that I would happily work for again. And…I can’t help but wonder…if someday this person will disappoint me, too.

Losing Perspective and Getting it Back

When we’re in the middle of challenging circumstances at work, it is easy to lose perspective.

When we’re in the middle of challenging circumstances at work, it is easy to lose perspective.

Under significant stress, we get tunnel vision. When our adrenal glands activate our flight or fight response, we narrow our focus to better deal with the threat at hand.

That’s great when we’re faced with immediate bodily harm. It’s not helpful when our bodies feel threatened every time we go to work.

When our attention is tightly focused on the stressful problem we’re experiencing, our ability to come up with solutions is reduced. Our brains draw on what we’ve already learned and experienced.

For example, maybe every time your previous manager yelled at you about a project you could calm them down by saying “Yes, I’ll get right to it”. Now your brain might be stuck on finding similar solutions, even if that approach doesn’t work at all with your current boss.

When you’re on high alert at work from constant stress, your natural flight or fight response is probably not going to help you deal with your manager, either. When they berate and demean you in front of your colleagues, you might feel an urge to throw a punch or to run out of the building. If you’re in control of your behavior, you’re most likely to freeze instead.

Many of us have felt stuck in a bad job. When we’re in a toxic workplace for a long time, our narrowed perspective can seem like our only reality. It might seem like there aren’t any good solutions. For every idea, we think of reasons why it won’t work. At times like this our best moments are when we’re distracted from thinking about our jobs.

How do we get perspective back once it’s lost?

The best advice I’ve learned is from the book Good to Great, by Jim Collins. In chapter four, Collins interviewed retired Vice Admiral Jim Stockdale, who survived nearly eight years as a prisoner of war in Vietnam. As he described his survival, Stockdale said, “You must never confuse faith that you will prevail in the end—which you can never afford to lose—with the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be.”

Stockdale had an unwavering belief that he would get out of captivity without ignoring the horrific situation he was in. He not only survived, but went on to complete his military career, work in academia, and write a book.

Having faith that you will prevail over your current work circumstances can be challenging when you feel like you’re in survival mode. But think of Stockdale. He was literally in survival mode and prevailed.

Can you believe that you will go on to a better job and leave your miserable one behind? I have talked to over a hundred people who have done this. They were call center employees, pizza deliverers, paralegals, tech workers, correction officers, teachers, government employees, among others.

In my own career, I once felt trapped in a stressful job where I felt miserable most of the time. I believed that I could quit and find a different job, but I kept thinking of reasons not to. I worried that a new job would have worse benefits, or that I’d have a long commute, or that maybe the good parts of my job should outweigh the bad. I worried about the unknown.

In my own career, I once felt trapped in a stressful job where I felt miserable most of the time. I believed that I could quit and find a different job, but I kept thinking of reasons not to. I worried that a new job would have worse benefits, or that I’d have a long commute, or that maybe the good parts of my job should outweigh the bad. I worried about the unknown.

I had to convince myself to accept “the brutal facts of my current reality”. This meant accepting that there were positive parts of my job that I would miss: a project that I loved working on, many coworkers, and the salary and benefits. I also accepted that the job was wrong for me and I needed to leave it.

It took a long time for me to reach that point, but once I did, my perspective changed in an instant. At the time, I was home sick and didn’t have the energy to do much other than rest. I remember reclining on my couch, staring at the walls of my home, my sanctuary. I suddenly realized that a big reason why I stayed in my job was that it paid the mortgage and other bills.

In that moment, the trap was broken. I knew I could find other work that paid my living expenses, and that staying at my job wasn’t worth the negative impact it had on my wellbeing.

From that moment on, ideas for work came to me without trying. My mind opened to new options, I started writing again, and stopped worrying about paying the mortgage. I was confident in the many positive possibilities that my future could hold.

That was many years and mortgage payments ago. Since then I have been on a whirlwind of adventures in business and writing that I could not have imagined when I was clawing at solutions from inside a small, weary point of view.

Empathy. Intention. Action.

I read this article today. It’s about one black woman’s experience at school and work. I don’t have the same experiences as her – it’s not my story. I don’t know exactly how she feels. I can try to empathize, though, and think about my intentions and actions.

When the author describes teachers and colleagues making racial insults, I don’t know exactly what she thought and felt in those moments. I imagine she was angry and frustrated because those are the feelings that I had when reading about it. It brought to mind what it felt like when I’ve attempted to stand up for myself to people who had authority over me.

It doesn’t take much effort to try to empathize with someone who is hurt.

Taking action is harder than empathy because there’s risk.

At the end of the article, the author refers to an incident at a Seattle Starbucks that is described on KUOW’s site as A man shouts racial slurs in a Seattle Starbucks. The silence is deafening. In a crowded coffee shop, only one bystander offered support when two people were verbally attacked and spit on.

Maybe the other customers were afraid they would say or do the wrong thing, so they did nothing. Or they didn’t want to draw attention to themselves. Or they worried if they offered to help, they would be asked to provide assistance that they didn’t want to give.

There’s risk involved.

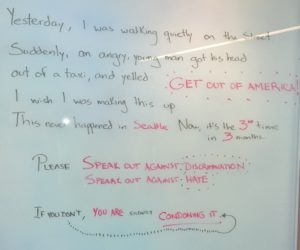

A couple of years ago I spent some time in an office building. One day I noticed writing on a whiteboard in a hallway. It said “Yesterday, I was walking quietly on the street. Suddenly, an angry young man got his head out of a taxi, and yelled, “Get out of America!” This never happened in Seattle. Now it’s the 3rd time in 3 months…Please speak out against discrimination. Speak out against hate. If you don’t, you are silently condoning it.”

Maybe the person wrote it hoping that people who haven’t experienced this kind of harassment will become more aware of it, have empathy for it, and offer support when they witness it.

The writing on the whiteboard was untouched for three days. Then a new message was added that said something like “I’m sorry this happened. I will speak up if I see it.” A couple other notes were added. The next day the whiteboard was blank again.

It wasn’t hard to empathize with the person who was yelled at from a taxi and asked us not to be silent bystanders.

It was hard, however, for that person’s coworkers to react – even through a few anonymous words on a white board.

It’s even harder to offer support to a stranger who’s been called racial slurs in a coffee shop.

These aren’t my experiences of hate speech. They aren’t my stories and it isn’t my place to end with a big statement about combating discrimination. But I can empathize. I can think about my intentions and actions. And maybe I can be brave enough to risk saying or doing something, even if it isn’t perfect.

I was stuck in stop-and-go traffic for almost hour this evening. I would rather have been home already, or at least driving at a steady speed, but wasn’t really annoyed. I was on the fastest route and there was nothing I could do to make traffic move more quickly.

I was stuck in stop-and-go traffic for almost hour this evening. I would rather have been home already, or at least driving at a steady speed, but wasn’t really annoyed. I was on the fastest route and there was nothing I could do to make traffic move more quickly.

Recent Comments