It’s OK to be Angry at Injustice

There was a time when I thought that anger was a bad emotion. We’re told to “cultivate peace in our hearts,” that “anger will eat you up inside,” and “to let it go.” Now I know it’s not that simple.

There was a time when I thought that anger was a bad emotion. We’re told to “cultivate peace in our hearts,” that “anger will eat you up inside,” and “to let it go.” Now I know it’s not that simple.

One of my favorite people that I’ve worked with gave me a new perspective about anger. We were talking about how a person with authority in our office treated people disrespectfully and mismanaged programs. This wasn’t a case of a little rudeness here and there; this was systematic bad management.

After venting to my coworker, I said something like “I should try to not get angry about this.” He stopped me and said, “There’s nothing wrong with righteous anger.”

I hadn’t thought of it that way before and it changed the way I viewed my feelings about the situation. I was reacting to injustice. Being aware of the problem and angry about it was better than pretending it wasn’t happening and that I should feel ok about it.

Anger has energy. If righteous anger fuels us to stand up to injustice, then it’s not a bad emotion. It’s a signal that our values are being violated and an energy to work towards change.

Keep Calm Before You Hit Reply

One time I was working on a global promotion with someone in another company that partnered with the one I worked for. We each had different contacts in our European offices, and emailed them back and forth while we tried to determine who exactly we needed to work with, and when we could speak with them. After a week or so, the person I had been working with stateside emailed me that we could share the details of the promotion at a reoccurring meeting with the exact European colleagues that we needed to talk to.

One time I was working on a global promotion with someone in another company that partnered with the one I worked for. We each had different contacts in our European offices, and emailed them back and forth while we tried to determine who exactly we needed to work with, and when we could speak with them. After a week or so, the person I had been working with stateside emailed me that we could share the details of the promotion at a reoccurring meeting with the exact European colleagues that we needed to talk to.

Great!

He forwarded the meeting invitation to me, and I quickly drafted a short explanation of the promotion and agenda for the next meeting occurrence, which I emailed to the meeting attendees.

What happened next was so awful that I still cringe when remembering it.

The meeting owner immediately replied to me and copied everyone who had been sent my original email, informing me that I was not permitted to hijack his meeting, I was completely unprofessional and he was going to tell my manager how rude I was, etc, etc. He wrote that he set up a new meeting series with a new conference call number that I wasn’t invited to, so there is no possible way I could join his meeting, ever. There were a lot of capitalized letters and exclamation points.

I was stunned. I got on the phone with the person from the other company to ask what happened. It turns out I wrongly interpreted his email to mean that he had organized our presentation with the meeting owner. What he meant was that the people we needed to speak with had regular meetings and we could try to get on their agenda.

Oh.

You know that saying, “When you assume you make an ass out of u and me”?

Yep.

I needed to do damage control but there was no way I was calling this guy. For one thing, there was a nine-hour time difference and it was too late at night to receive calls at his location. Also, I didn’t want to experience over the phone the same level of rage that came through his email.

I started drafting an email response but was so upset that it was difficult to know what to write. I was very sorry for my screw up but also defensive because I had acted in good faith. At the heart of the matter, the joint promotion I offered would help increase sales of a product that none of them were meeting their forecasts for.

I was also angry and offended by his words, and humiliated that he blasted me with 30 other colleagues on the email. I wasn’t ready to appreciate the irony of him labeling me as unprofessional.

So, my email response was not coming along very well. I got up from my desk in search of my manager or someone else who could advise me. Luckily, I ran into Jill. She is to this day the most unflappable business person I’ve ever met. I told her what happened and asked her advice.

She suggested that I reply to everyone on the email and in as few sentences as possible, explain my mistake and apologize – but to strip the emotion out.

I went back to my computer and wrote several more drafts until I had a version that sounded neutral. I hit “send”, went home, and dreaded what I would find in my inbox the next day.

I only received one email reply, from a colleague of the meeting owner. He wrote that he was embarrassed by his coworker’s email and apologized on his behalf. I never heard from the meeting owner again and forgot his name a long time ago.

What I remember, though, is how effective it was to reply to a heated email in a completely neutral tone. If I had responded in a way that sounded defensive, offended, or angry, I would have been adding fuel to an emotional situation. On top of making a careless mistake, I would have appeared as bad-tempered as the other guy. Instead, I looked mature and rational by taking responsibility for the situation and briefly explaining why I thought I had been on point for the meeting.

I try to remember to read my email responses out loud whenever I’m responding to someone else’s strong emotions. If I sound mild to my own ears, my text is probably fine. And when its about participating in someone else’s meeting? I do not assume.

Your Truth at Work

Making good decisions about our words and actions is part of having – and keeping – a job.

Making good decisions about our words and actions is part of having – and keeping – a job.

Whether working with customers, coworkers or employers, there’s a certain amount of self-editing that is required to get along with people and sufficiently meet the expectations of the people that pay you.

Choosing to not say exactly what you’re thinking is a good decision much of the time. Spewing unfiltered frustration damages relationships and your reputation.

At the other end of the spectrum, censoring yourself too much isn’t constructive either. Constantly saying what your manager wants to hear, when it isn’t what you believe, is exhausting. Going along with unethical decisions out of fear probably won’t erase your fear – but will add feelings of guilt. Holding back when you have an opportunity to contribute deprives both you and your organization of your ability to make an impact.

Modifying your behavior at work to the extent that you aren’t being true to yourself isn’t healthy. It’s stressful and depressing.

In some workplaces, there may be room for adjustment. Maybe you can say what’s important to you by approaching the topic in a way that reduces the risk of upsetting the people you work with. Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People has great tips for situations like this. Taking a Dale Carnegie class is even better because you get to practice these skills.

If attempting to influence the organization doesn’t work and you’re currently not able to get a different job, you still have control over something: your truth. You might need to smile and nod for self-preservation, but you can acknowledge to yourself what you see, hear, and believe. Don’t let them steal your truth.

We Didn’t Get Here From Hard Work Alone

It’s easy to attribute hard work to any kind of career success we have.

It’s easy to attribute hard work to any kind of career success we have.

“I worked hard in high school; that’s why I got into this prestigious university.”

“I worked hard in college; that’s why I was hired at this great job.”

“I worked hard on this project; that’s why I got a promotion.”

OK, so we did our homework and studied for tests. We carefully completed the applications and were scrupulous with our resumes. We figured out what our managers wanted and delivered it.

It was hard work.

But.

That hard work is often the effort used to capitalize on our fortunate circumstances. We can convince ourselves that we deserve our success, that we earned it, because we put a lot of time and focus into achieving it.

Hard work is honorable. Working towards a career goal is admirable.

Yet.

Hard work alone did not earn us our achievements.

Someone read and accepted our college application. Someone permitted us to interview for the job and someone made the decision to hire us. Someone favored us with the promotion or raise or award.

Someone decided we were qualified, acceptable, and perhaps more worthy than others aspiring to the same position.

Because they are human, those someones have their own ways of evaluating us. Their experiences and their environment influence their perspectives. They may be aware of their ingrained biases and work to overcome them. Or they may unaware of unconscious biases, or disbelieve that they exist.

Unconscious bias does exist.

Overt bias also exists in plenty of people who believe certain people are inferior, threatening, or sinful.

If we are a combination of any of these factors, we have benefited from other people’s biases regardless of whether it was intentional:

· White

· Heterosexual and cis

· Male

· Tall (unless you’re a jockey)

· Body and face considered normal and attractive by societal standards

· Attended decent primary and secondary schools

· Wealthy parents

If we have some of these characteristics – and I do – we have benefited from them.

If we don’t admit our undeserved advantages, we get to believe we earned our slot by working hard. We also get to believe that other people should work harder if they want what we have and it’s their own fault if they don’t. We can then support this line of thinking by pointing to people who achieved great success despite the odds.

It’s very American to hail the underdog achievers and the rags-to-riches stories. However, these examples stand out precisely because they are not the norm.

When we’re surrounded by other privileged people and the exceptional outliers, it’s easy to assume everyone else’s lack of success is due to a lack of effort. We might even believe that if our advantages had been stripped away, we would still be accomplished.

Believing it doesn’t mean it’s true.

I acknowledge my privilege and the role it plays in my education and career opportunities.

Your Ethics Can Get You Fired

Maintaining a positive reputation at work means that sometimes you don’t speak up when something’s wrong. We all know the sayings, “don’t rock the boat” and “pick your battles.” When the issue goes beyond a gray area, or a slight bending of the rules of the employee handbook, you’re in a tough position.

Maintaining a positive reputation at work means that sometimes you don’t speak up when something’s wrong. We all know the sayings, “don’t rock the boat” and “pick your battles.” When the issue goes beyond a gray area, or a slight bending of the rules of the employee handbook, you’re in a tough position.

Several years ago I had a conversation with two mid-career lawyers about sexual harassment in the workplace. Both of them said that they would not tell their firm’s HR department or file a complaint if they were sexually harassed. They were sure that they would be fired in retaliation and black balled in the legal community, preventing them from getting a new job in their field.

I asked what they thought about the moral obligation to report issues like this. Because if nobody takes a stand against harassment and discrimination crimes, then they will keep happening, both to the current victim and others. The two lawyers didn’t hesitate to say they wouldn’t ruin their careers over it.

Over the years I’ve heard many variations of that conversation, but this stood out because the people were lawyers. They understand the law, their rights, and the process to seek justice if wrongfully terminated.

They also understood the personal consequences of reporting a crime and decided it isn’t worth it.

That’s bleak, and probably why we admire some whistleblowers who expose large scale crimes in their workplaces. Calling out illegal activity is a huge personal risk. Up until the point when whistleblowers are national heroes talked about in the media, they might be considered by their company’s peers and managers to be rats, tattlers, trouble makers, whiners, complainers, and ungrateful losers who should have been happy they had jobs in the first place.

They might be called all of those things and also be freshly unemployed. With a bad reputation that makes it difficult to be hired elsewhere.

Other people told me stories about being instructed by their managers to lie to investigators about crimes they witnessed. One man admitted that he lied under oath in trial court because his supervisor demanded that he do so or else lose his job.

Where do you draw the line between self-preservation and ethics?

I’m guessing most of us think we would make the ethical choice if we were in situations like that. But when people are actually in a position to lose their livelihoods, I doubt it is such an obvious decision.

I’m glad there are some people brave enough to sacrifice their personal wellbeing to stand up to workplace crimes.

Choosing Who to Confide In at Work

The people you work with are often either the best or the worst parts of your job. When those relationships are positive, it can make you more productive, successful, and happier.

The people you work with are often either the best or the worst parts of your job. When those relationships are positive, it can make you more productive, successful, and happier.

When the other parts of your job aren’t going well, having trusted colleagues to confide in can help you get through the day.

Whether they are work friends, your staff, your boss, your peers, people in organizations that work with your organizations, Human Resources – anyone involved with your work – think twice before sharing confidential information. Telling the right person your secrets can strengthen your bond and make the relationship more important to both of you. Telling the wrong person can damage your reputation and career.

Who to trust with specific information can depend more on the individual’s personality than their* position in the company, but there are some common factors to keep in mind.

When You’re Looking for a New Job but Haven’t Accepted an Offer Yet

Your boss: Almost always no.

If you have a positive relationship with them, you might think they would appreciate knowing that you intend to leave before you turn in your two weeks’ notice. However, generally level-headed people can still take it personally, as though you are leaving them not the job. They might also be resentful that they will have to deal with hiring and training a new person and managing your workload until the position is filled. If your news overlaps with performance review timing, you could be punished for disloyalty.

There are only two circumstances when telling your manager may be better than keeping it to yourself. The first is when your boss has explicitly encouraged you to grow your career by taking advantage of job opportunities. The second is when you’ve witnessed your manager supporting other team members who have left the team.

Your employees. No.

Telling your staff that you plan to leave will make them worry about their own jobs.

Your peers. Usually not.

Even your work friends may be jealous or not want you to change the dynamic in your organization. You might feel guilty withholding this information, as though you are being a bad friend. It is more useful to remember that a lot of things can go sideways until you have a signed offer in your hands. It’s much better to wait and share the good news once you’ve landed a position.

The exception is when you need a work reference and can count on a peer to help sell a recruiter on your capabilities.

Health Issues

Your boss, your employees, and your peers: It depends on their personality.

For every person I know who had workplace support through a significant illness, I know of another person who was made miserable during the experience, or even pushed out of the company.

If you’ve got doctor-ordered treatments that take you away from the office or cause obvious physical changes, you don’t have a choice about whether to keep it a secret or not. With other illnesses, it can be difficult to know if you will be supported or punished. The best you can do is evaluate the level of empathy your management has shown for you and others.

You may be able to confide in your manager but keep it a secret from your peers and staff.

Human Resources Issues

Your boss: If your workplace requires it and/or they will actually help you.

If there’s something going on that violates company policy, it’s not paranoid to consult the employee handbook to understand your obligations. If for example you witness employee theft, the policy likely requires you to step forward or else be punished if caught.

If you are thinking about going to your HR department about a workplace issue, remember that they are there to protect and support the organization first. Anything your report is likely to be shared with your manager.

It’s tough to be in a situation where reporting an issue may be the ethical thing to do but puts your job at risk. The media reports on big whistle-blower cases and employee lawsuits. We don’t hear about the other thousands of instances when an employee is forced out or fired for calling attention to a problem.

Your employees: Nope.

Your peers: Probably not.

Unless you and your peers are collectively talking about an issue, it is in everyone’s interest to keep it to yourself. You don’t want to drag other people into situations that could put them at risk or get you in trouble for revealing information that you’ve been asked not to talk about.

Other Personal Stuff

Your boss, your employees, your peers, and everyone else in this world: Share with caution.

When you have Other Personal Stuff impacting your life, of course you need to talk about it with others. Talking helps alleviate some of the burden, and unless you’re a robot, you need some support.

Just be careful who you confide in. People that are otherwise pleasant and even caring towards you might react in unhelpful ways.

Of course if you have any doubt that they might share your personal information with other people: avoid! It’s not worth it. People love to gossip. Don’t become their story of the week.

Many people do not deal with Other Personal Stuff very well. It might be too uncomfortable for them, or they don’t know how to respond. That sucks, but it is kind of understandable. Some people just don’t realize that when in doubt, any of these work: “I’m sorry to hear that. That sounds stressful. Are you ok?”

Worse than clueless but benign people, though, are people who respond so badly that they make your situation worse. Bad responses might be downplaying or denying your situation, victim-shaming, or telling you how you should be coping. On top of whatever issue you’re experiencing, then you have to deal with being blamed or shamed, feeling betrayed, or feeling alone in a situation where you need help from others.

Unfortunately, it can be hard to tell who is unsafe to confide in until it is too late. Friends and family members are just as likely to respond badly as your coworkers. So don’t spill your guts. If there’s someone you feel compelled to share your story with, get a feel for their reaction before you provide the details.

With all people and all topics

Remember that once you tell anyone personal information, you lose control of it and who else they might tell.

*I’m using the plural for he/she/his/her because using “he” alone is gender-unfriendly and writing “he or she” is annoying.

Dealing with career disappointment

It is disappointing when you are not where you want to be in your career.

Maybe you thought by the time you were this age that you would be managing a department or earning a milestone salary.

Maybe you hop ed that after working this many years in your organization, that you would have been promoted by now.

ed that after working this many years in your organization, that you would have been promoted by now.

Maybe you expected that after the education and training you spent time and money on that you would enjoy your profession – but you don’t.

Or you’ve bounced from job to job and still don’t know what kind of job would make you happy.

I’ve met so many people that are frustrated with their careers for these reasons. The ones that are currently experiencing it often tell me that they feel defeated. They aren’t hopeful that they will ever find career satisfaction. It can be hard to believe it when you’re in the murky depths of a job disappointment, but I can tell you with certainty that is that there is still time for you.

You could still achieve the specific career goal that you have right now. There could be one small shift in your organization – a new manager or a new set of responsibilities that changes everything.

One man that I met about 10 years ago could not seem to get a break in his workplace. Let’s call him John. Year after year, John got not-so-great performance reviews and it seemed like he wasn’t going to move up the career ladder at his company – his career was stalled. Then out of the blue, John’s manager left the company and his new manager took an interest in him. He gave him recognition for his work that he hadn’t had before and praised him to other managers. That year, he finally got promoted and apparently continued to do well – very well: I ran into John last year and learned that he still works for the same company and is now an executive.

The small shift could come from something as simple as on-the-job training that you’re required to do.

A woman that I know, “Abby”, was content in her marketing job at a medium-sized company. Then her manager sent her to a training seminar to learn process improvement that would help the department run more effectively. Abby returned from the training lit up with passion for the techniques she learned.

I remember how excited she was when she talked about it. Her perspective of work went from “this job is ok” to “I know what I want to do with my life.” She kept finding ways to apply her new knowledge. At first, this was within the company she worked for. Then Abby sought out more training on her own, met people in the process improvement field, and through those connections got a full time job doing work that she loved.

If you haven’t found a meaningful job yet, you still can. In my research about people quitting jobs, I heard from dozens of people who were frustrated and exhausted with their work, yet found their way into career satisfaction. I spoke with people in their twenties and people in their late sixties – and all the decades in between. It’s not too late!

Many of the people I talked to could not have imagined their careers they have today back when they felt stuck and unhappy. There were no overnight changes. Instead, they followed their interests one step at a time and discovered opportunities along the way.

If you don’t know where to start, the most useful advice that I learned was to just learn more about whatever topic it is that you’re interested in and see where that leads. This might mean going to a seminar on whatever topic you are curious about. Or looking up information about it on the web or reading a book. Or volunteering for a cause that you care about. I’ve met full-time, paid care-givers at three different animal sanctuaries who started as casual volunteers. They are some of the happiest job-changers that I know.

Just take one step in the direction that interests you. It might lead you down the hallway of your current organization into a slightly different role, or into the dream job you never knew you wanted.

Dream Big, They Said

Remember when we were little kids and we were told we could do anything we set our minds to? We heard it mostly in grade school, but also in after-school programs and from parents.

Remember when we were little kids and we were told we could do anything we set our minds to? We heard it mostly in grade school, but also in after-school programs and from parents.

We were told inspiring accounts of people who achieved great things. We learned of career options from astronaut to president and told we could have those jobs. We were taught about Mother Theresa and Martin Luther King Jr and told we too could do big work with a big impact that helped many people.

We were told to dream and work hard. We could do great things in our lives. We just had to make up our minds and go for it.

Teachers and the others – they can’t very well NOT say those things. Where would we be if we hadn’t been told to have dreams and try to reach them?

I wish, though, that we had been taught what to do when things go wrong in our pursuit of our big dreams. And what to do when life squishes our dreams before we even really attempt to achieve them.

I think it happens as early as high school – when we trade in our grand ideas for more practical matters. Our awareness grows. We understand what we hear on the news and its implications in our own lives…jobs and joblessness, natural disasters, war…

There are also timelines to consider. Preparing for the first job out of high school, or attempting to get into college and then deciding what to study. And then graduating and needing a job and a place to live.

After college I wasn’t dreaming much. I enjoyed my life and dove into the beginning of my career, but looking back, I can say my dreams were replaced by goals.

And my goals – at least the biggest two that I accomplished in my adult life so far – didn’t even come from a strong desire within myself to achieve something meaningful.

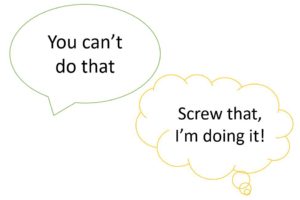

Instead, they were inspired by obstinacy.

It is true that since college, if not earlier, I vaguely expected to get an advanced degree at some point in my life. However, it wasn’t until I was rejected from a year-long marketing certificate program that I was motivated to get an MBA. My exact thinking was, “Seriously, I was turned down for a certificate? Screw them, I’m getting a master’s degree.” Some rigorous GMAT prep and five years of school later, I had my degree. Ultimately, I was glad I was refused participation in the certificate because it turned out to be a fraction of what I wanted to learn and was capable of achieving.

My second example is only slightly different, in that I hadn’t thought about home ownership as a goal at all. I was about to give up my apartment to move to another place with someone when circumstances changed and obstinacy kicked in again.

My second example is only slightly different, in that I hadn’t thought about home ownership as a goal at all. I was about to give up my apartment to move to another place with someone when circumstances changed and obstinacy kicked in again.

I decided I would make housing plans on my own and buy a place instead of renting. I made a budget in excel, put as much as I could into the down payment and fees, and then I owned a home.

I didn’t need to learn to use rejection and setbacks as motivation but I think it should be taught. I hear too many stories from older writers and artists who put down their pens when they were young adults because somebody told them they weren’t talented. It seems like it would be a very useful lesson plan to prepare kids for when they are told no, they can’t, they aren’t good enough, to muster a “screw you” attitude and pursue their art anyway.

Another skill that I wish I had been taught in school is how to channel disappointment into something useful. I get depressed by civic issues of inequity and discrimination and need more than the grade school equivalent of a lemonade stand that raises money for these causes. My stabs at educating myself, speaking up, and seeking out groups to participate in seem the right steps for now, but I was floundering for a long time.

The lemonade stand fundraiser is great to show little kids that they can take initiative and tangibly provide support for causes. But then the cups are put away, the money is donated, and life goes on. What’s missing is sustained effort, and follow-up to see what impact was made. An analysis to determine what about the effort was successful and what can be done to improve. Or how to translate lessons learned into the next effort.

Some of my good friends share this sense of civic-work malaise. We have a sense of being pushed to put our skills and experience to better use. Even people who are working in non-profits or who are on the board of multiple civic groups are unsettled and feel there is more they should be doing. There is a limit to how many action committees a person can reasonably join, so it seems failure to achieve the desired impact is the problem. We’re falling short of our big dreams to make a big impact.

Wouldn’t it be great if we were taught throughout school how to be patient and sustain efforts over a long period of time, even when we don’t see the results we want? I remember being taught about Abe Lincoln’s personal and professional setbacks before he became president. He had business debts that took years to pay off, was a self-taught lawyer, and lost his first attempt to win an Illinois state legislative position.

What isn’t clear is what motivated him to keep pursuing his dreams.

I wonder if he was driven by a belief that he had something to offer people. Maybe he resolved to keep trying, and to look for ways to use his abilities to be of service.

What we do know is that he said yes to opportunities. Clearly he didn’t let fear of failure prevent him from going into business, becoming an attorney, or running for public office. After each misstep, he came back with resilience. Whatever doubts he might have had about his abilities to perform in those professions didn’t stop him from showing up and doing his work.

I didn’t learn these things in school, although I wish I had.

I’ll keep using obstinacy as fuel when people tell me I can’t do something I want to do. I’ll try to be patient with setbacks and keep ahold of my belief that I have something to offer, even when I don’t see progress.

You too, ok? When someone tells you no, go ahead and prove them wrong.

And keep the faith. You’ve got something to offer.

The Coffee Can Method of Getting a Dream Job

Elizabeth Gilbert tells a story about a woman who dreamed of traveling the world, but was an impoverished single mother. The woman put a single dollar bill in a coffee can every day. As Gilbert tells it, the woman figured that they had so little money that one dollar didn’t make a difference. After many, many years, once the kids were grown, the woman finally had enough money saved to travel on a cargo ship that visited a number of different ports. She sustained her goal for two decades, and achieved it.

Elizabeth Gilbert tells a story about a woman who dreamed of traveling the world, but was an impoverished single mother. The woman put a single dollar bill in a coffee can every day. As Gilbert tells it, the woman figured that they had so little money that one dollar didn’t make a difference. After many, many years, once the kids were grown, the woman finally had enough money saved to travel on a cargo ship that visited a number of different ports. She sustained her goal for two decades, and achieved it.

I like this story. I especially like to remember it when it my goals seem distant and so difficult to achieve – specifically, publishing my self-help book for people that want to quit their jobs. It will happen, someday!

I also like to remember the coffee can story when I think about all of the people who are unhappy in their jobs, who feel stuck and have very real obstacles that make it difficult to quit. Their current jobs have health insurance for their families and the jobs they want do not. Their current jobs pay the rent and the daycare and the jobs they want would not cover those bills. Their current jobs are in the towns where they share custody of their children with their ex-spouses, and the jobs they want are in other parts of the country.

These are real blockers.

Still, getting unblocked is realistic. Saving money is fundamental in creating more choices for work. It can take a long time, and setbacks from unexpected expenses are frustrating. Yet it is possible.

There are other possibilities for getting unstuck, but they too can be long journeys. Doing a “side hustle” is the safest, most risk-adverse way that I know of to launch a new career. However it takes energy and motivation to spend time on a side business before going to a day job in the morning, and to work on it at night and on weekends. Sometimes it might seem worth it, and other times it might seem too exhausting.

I relate to this particular struggle. My drive to complete my book and shop it out to agents and publishers competes with my desire to have downtime and rest. In my case, choosing rest means that it will just take longer to complete my goal.

Hopefully not twenty years.

There are also ways to lessen the pain of the current job while working towards the dream career. Building confidence through honing skills and racking up “wins” by completing projects to the best of abilities helps. Fine-tuning resumes and LinkedIn profiles is a good idea for everyone. Expanding life outside of work to include hobbies, friends and fun is a great way to keep a miserable job from feeling like it is all-consuming.

We hear all the time that “life is short”. But time is relative, so life can also be long. It’s okay if you didn’t start putting money in the coffee can ten years ago. You can start now. You can start any time.

The job you want is there for you, even if it is far enough away that you can’t quite believe it yet.

Recent Comments